Fine’s romp through the fields of neurosexism is sandwiched between two other sections; in the first, she explores the unsexy, low-tech, but primary causes of gender differences in achievement: the persistence of discrimination, subtle and blatant, that convey the message to women – “You don’t belong here”, and the institutional rules, explicit and implicit, that impede advancement – or make it possible; after all, the international rise of women in law, medicine, science, bartending and the military did not occur because their brains became less lateralized. The final section examines the socialization of children and the phenomenon that draws so many parents to the notion that sex differences are innate: the sex-stereotyped play choices and behaviours of their toddlers. Parents aren’t wrong in what they observe. They are wrong only in assuming that their child’s preferences at the age of three, four or five has anything at all to do with what that child will grow up to become.

Friday, January 28, 2011

Neurosexism

Tuesday, January 25, 2011

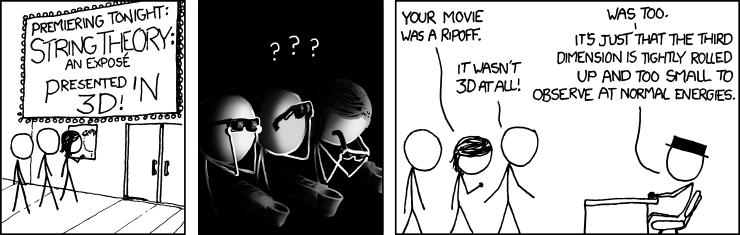

Argument from Partial Understanding

- We have not proven beyond all doubt that X is true.

- Therefore, X is probably not true.

- I would hardly be able to believe it if X were true.

- Therefore X is not true.

- If X were true, then I would know it were true (or I would understand claim X).

- I don't know for a fact that X is true (or I don't understand claim X).

- Therefore X is not true.

- Realists believe in the literal truth of scientific statements about both observable and non-observable (or theoretical) entities, while anti-realists grant this level of belief only for statements about observable entities.

- Bridges are observable, concrete is observable, and cracks in concrete are observable; molecules and molecular bonds are not so observable.

- I'm an engineer, and I understand bridges, concrete, and stress fractures; I never really understood what was going on in my organic chemistry class.

- Therefore engineers like me should be anti-realists.

Thursday, January 20, 2011

Johnny Can't Write

Cursive writing is "not addressed as a skill anywhere in Kentucky's core content, and there are so many other things that are," said Terry Price, director of elementary education for Bullitt County Public Schools. "Students need to be able to sign their name and be able to read it, but I think we'll get to a point in the future where it's not necessary at all."

For now, however, most educators are still teaching cursive writing, said Vanderbilt University professor Steve Graham, who conducted a study on the subject in 2008. He and other researchers surveyed about 170 first-, second- and third-grade teachers across the nation and found that 90 percent taught handwriting.

The time spent on those lessons averaged about 60 minutes a week, but some spend as little as 10 minutes a week on it, and the majority of teachers said they didn't have any real training in how to teach penmanship, Graham said.

Tuesday, January 18, 2011

Academic Discrimination and Pregnancy

Climate Change and Disease

The American public's concern about climate change continues to decrease even as the evidence supporting the urgency and potentially harmful implications of the problem grows. Some studies have argued that this disconnect has as much to do with psychological responses and defense mechanisms as it does with serious reflection.

Monday, January 17, 2011

Paradigm Shiftyness

An astrological controversy erupted online Thursday after a newspaper article erroneously suggested that the dates that determine the Zodiac signs had shifted by about a month, throwing millions of believers into self-doubt and panic.

Sunday, January 16, 2011

Teaching Philosophy, Early

Harry, like his author, came to believe that the most important thing in the world is thinking.

“I know that lots of other things are also very important and wonderful, like electricity and magnetism and gravitation,” Harry said. “But although we understand them, they can’t understand us. So thinking must be something very special.”

Friday, January 14, 2011

Language Shapes--or Reflects--Reality?

Does treating chairs as masculine and beds as feminine in the grammar make Russian speakers think of chairs as being more like men and beds as more like women in some way? It turns out that it does.

...

I have described how languages shape the way we think about space, time, colors, and objects. Other studies have found effects of language on how people construe events, reason about causality, keep track of number, understand material substance, perceive and experience emotion, reason about other people's minds, choose to take risks, and even in the way they choose professions and spouses. Taken together, these results show that linguistic processes are pervasive in most fundamental domains of thought, unconsciously shaping us from the nuts and bolts of cognition and perception to our loftiest abstract notions and major life decisions.

Thursday, January 13, 2011

All men are created equal

Another thought on language and gender.

Sentences such as "all men are created equal" are ambiguous. Does the word "men" refer to men, or does it refer to men and women? Usage today is mixed, with most people saying "people" when they want to refer to men and women, and some people using "men" to refer to all members of humanity.

But when this phrase was written in the Declaration of Independence in 1776, to announce the value of democratic government and speak against the divine right of kings, it did refer to men specifically, and in particular to white, property-holding men. For this reason, Elizabeth Cady Stanton referred to but modified the phrase in her 1848 Declaration of Sentiments to say that "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men and women are created equal."

Some students in my feminist theory class say they see no harm in referring to humanity as men. One argument given in favor of this practice is that everyone already knows that 'men' in this context means 'everyone.'

However, the question of whether 'men' really means 'men and women' (or even 'white men and black men') becomes politically relevant in the context of originary interpretations of the Constitution. Originalists believe that the Constitution grants only those rights which were actually intended by the people who wrote it or who approved its later amendments.

At times, Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia appears to be a strict originalist. For instance in an interview he recently denied that the 14th amendment can be used to protect the rights of women (in spite of decades of Supreme Court precedent). While saying that it could be used to deny them those rights.

From what I can tell in this interview, he does not deny that women can be given civil rights. But any rights that women have (other than the right to vote), would have their origin in legislation. Unlike men's rights, they are not constitutional rights.

Here's part of what Justice Scalia has said:

Certainly the Constitution does not require discrimination on the basis of sex. The only issue is whether it prohibits it. It doesn't.

More here:

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/darren-hutchinson/post_1524_b_804382.html

Wednesday, January 12, 2011

Gender embedded in language